by Sumiko Kobayashi

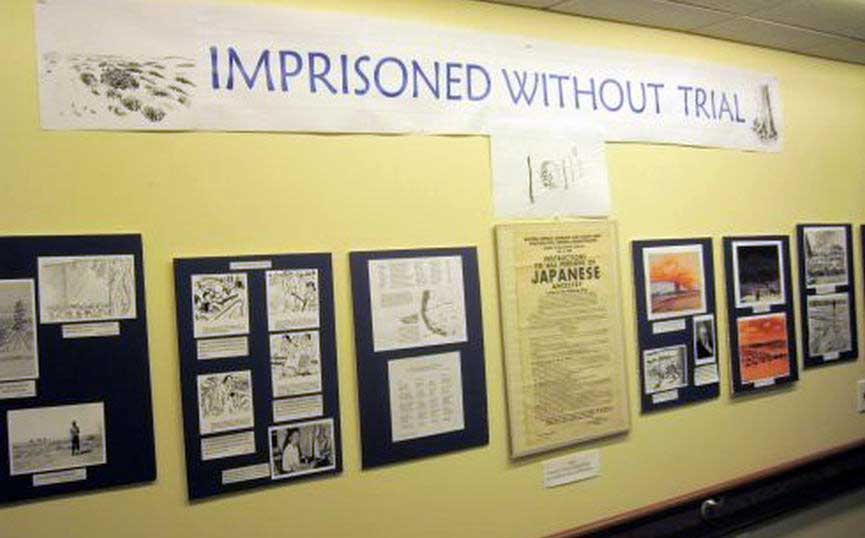

In October 2008, as part of the celebration of Tak Moriuchi’s life, Sumiko “Sumi” Kobayashi prepared a display in the Medford Leas Gallery called “Imprisoned Without Trial.” Every photograph and illustration on this page is from the exhibit. This version adds depth by providing more information about the images and links to relevant Internet resources.

(Note: in most cases you can click on a photograph to see a larger version.)

December 7, 1941

While the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on that fateful day affected the lives of every American then living, it had special consequences for Japanese Americans living on the west coast of the United States.

On the day after the attack the FBI and local police visited the homes and businesses of Japanese families, looking for contraband items like guns, cameras, short-wave radios, and took into custody community leaders: the leaders of Kenjin-kai (mutual self-help societies), Buddhist priests, and Japanese language teachers. It was literally the dreaded knock on the door at night. One of those taken away from their families was my father’s employer, a successful rose and carnation grower in San Leandro, California. For a long time his family did not know where he had been taken and when they would see him again. Fortunately he had a young adult son who was able to carry on the business until he leased the nursery and voluntarily evacuated his family away from the west coast.

In the absence of martial law, Japanese were placed under a curfew, 8 p.m. to 6 a.m., their assets were frozen, and travel beyond a radius of five miles required written permission from a U.S. attorney.

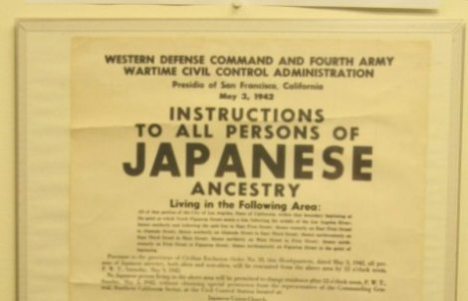

In the 2½ months after December 7, the Japanese communities waited apprehensively as Japanese military successes in Asia fueled fears of an attack on the mainland of the United States. Finally their uncertainty was resolved when President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 (EO) on February 19, 1942, which gave the U.S. Army blanket authority to move civilians out of the Western Defense Command. The EO makes no mention of “Japanese” but everyone knew it was intended to apply only to Japanese, aliens and “non-aliens” (citizens) alike, while German and Italian aliens were given individual hearings. Two arguments put forth for evacuation were that it was not possible to tell the loyal from the disloyal, and that the Japanese were removed for their own protection. The main argument given was “military necessity.”

The Army’s Wartime Civil Control Administration (WCCA) organized the removal of all Japanese from Washington State, Oregon, California and the southern third of Arizona. Infants to seniors, immigrant aliens and American-born citizens alike, were taken to temporary assembly centers (map) at horse racing tracks hastily converted to living quarters, and fairgrounds—existing facilities able to house and feed a large number of people. Evacuees were assigned a family number (example 21518) and instructed to bring with them only what they could carry in their two hands. Everything else had to be sold at distress prices or placed in government warehouses. Pets had to be left behind. Families were picked up by the Army at designated points and taken in buses guarded by soldiers armed with rifles and fixed bayonets to assembly centers. The centers were guarded by armed soldiers around the clock, and visitors had to speak to their friends through a 15-foot high fence. Two-thirds of the evacuees were American citizens. The average age of those evacuated was 18.

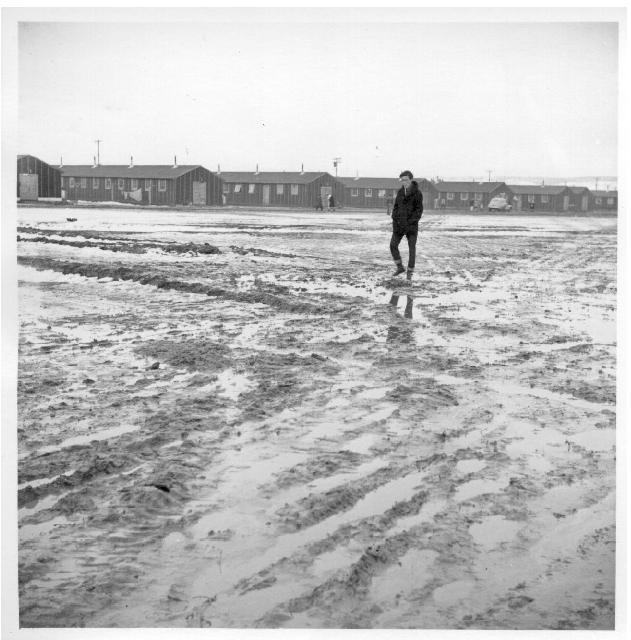

While the Japanese families were held in assembly centers, ten semi-permanent relocation centers (map) were being built on government-owned land; some were on Indian reservations. They were in eastern California, Idaho, Wyoming, Colorado, Utah, Arizona and Arkansas, each designed to hold 8,000 to 10,000 individuals in barrack cities. After the initial evacuation phase, the job of running the detention centers was turned over to a civilian agency, the War Relocation Authority (WRA).

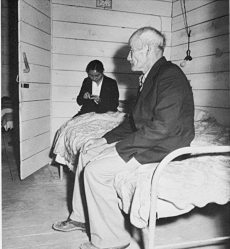

One of the first casualties of evacuation was individual and family privacy. Life in the relocation centers was communal. In residential blocks 12 barracks surrounded a central mess hall and laundry/bathroom building. The 12 barracks for sleeping were divided into apartments of different sizes for different size families, one room to a family. Another casualty was parental control over their children as young people congregated in peer groups. Some young men went to more than one mess hall to eat meals.

Each camp had a hospital, high school, several elementary and nursery schools and Protestant, Catholic and Buddhist churches. Each camp had a Project Director with a Caucasian staff, who lived in their own compound, but the bulk of running a “city” of 8,000 to 10,000 persons fell to the evacuees themselves.

The entire residential area was about one mile square surrounded by barbed wire with guard towers at intervals with searchlights pointed inward. These were manned around the clock by a small contingent of soldiers with guns, who were housed in their own compound outside the main camp area.

Within the confines of the barbed wire residents attempted to duplicate the community they had left behind. Besides performing the day-to-day tasks of running the camp, the evacuees organized classes for arts and crafts, poetry, and other hobbies, ran talent shows, held dances for the young people, showed current movies in the recreation halls, and organized baseball, football and basketball teams which later played local high schools. Every camp had a mimeographed daily newsletter and sometimes a literary magazine.

Pursuant to their Quaker values the Society of Friends was one of the few groups that sought to help the evacuees. The American Friends Service Committee send layettes to all the camps for mothers of newborns. One of the mothers who received such a layette is Florence Ishida, a Medford Leas resident in Assisted Living. Quaker individuals like Herbert Nicholson were loved by evacuees for bringing in items that evacuees could not obtain themselves, to demonstrate that some Caucasians had faith in them.

As the tide of war turned in favor of the United States, the authorities in Washington, D.C., and the camps, felt the individuals confined behind barbed wire should be allowed to leave the camps and resume a normal life so that a permanent dependent population would not be created. One of the first groups to leave was college students. A group of educators, including the President of the University of California at Berkeley, organized the National Japanese American Student Relocation Council to move students out of the camps and onto college campuses away from the west coast. John W. Nason, President of Swarthmore College, was named President of the Council. The American Friends Service Committee, headed by Clarence Pickett, was the working arm of the program. Tom Bodine, a conscientious objector, was its field director, who visited all the camps, interviewing prospective students and urging them to take advantage of the opportunity. William Marutani and Sumiko Kobayashi left the relocation centers for Dakota Wesleyan College and Drew University with the assistance of the Student Relocation Council.

Others followed as employment opportunities opened up. John Seabrook, the “Henry Ford of Agriculture” pioneered the frozen food industry in South Jersey. He had contracts with the armed forces to supply frozen vegetables, but because of the draft, enlistments and war industries, labor was in short supply. He sent recruiters to all the camps, inviting them to work at Seabrook with a promise of employment and housing. A scouting team from the Jerome Relocation Center visited Seabrook and reported favorably on the offer. Soon a stream of evacuees from all the centers arrived at the small town in rural New Jersey. Many children graduated from Bridgeton High School and went on to colleges and careers elsewhere. Ellen Nakamura and John Fuyuume established the Seabrook Educational and Cultural Center in Upper Deerfield, NJ, which tells the story of the multicultural, multi-ethnic “global village” that existed for a time in the area. The story of Seabrook is told in the 70th anniversary edition of the New Yorker magazine, February 20-27, 1995.

The Army, which had taken guns away from Japanese American soldiers when the war began, went to the camps to recruit young men and women. Reluctantly at first, the evacuees joined the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, the all-Japanese unit that received the highest number of decorations for a unit of its size in World War II. Others, especially the Kibei, men born in the U.S. but who grew up in Japan, were recruited for the Military Intelligence Service (MIS) to serve in the South Pacific and later with the Occupation in post-war Japan. Residents Minoru Endo and William Marutani were members of the MIS.

William M. Marutani was interned at Tule Lake, CA and then relocated to Dakota Wesleyan in South Dakota. He was a Philadelphia Common Pleas Court Judge, Civil Rights Volunteer, and a member of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians. His widow, Victoria Marutani is one of three Japanese-American residents of Medford Leas who were not interned. Vicki was a nurse in occupied Japan when she met Bill, who enlisted the help of his Congressman to enable her to enter the U.S., opening the door for other US servicemen to marry Japanese women.

Another Medford Leas resident, the late Minoru Endo, was interned at Topaz, UT and relocated to Minneapolis, MN. Endo was in the Military Intelligence Service (MIS), an Instructor at MIS, and served occupation duty in post-war Japan. He later became Vice-President of Mikasa, Inc. His wife Ayako, a Medford Leas resident now deceased, was also at Topaz. She relocated to MIS Ft Snelling, MN.

The camps were emptied and the camps closed in 1945.

The Japanese Americans tried to restart their lives, putting the painful past behind them. Many never told their children where they had spent the war years. The children often learned of their families’ past when they learned about internment in school and asked their parents about it. Growing up with the civil rights movement, the younger generation led the way in demanding justice for the violation of their parents’ constitutional rights.

The first of the ten amendments to the Constitution of the United States known as the Bill of Rights reads:

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.

At its national convention in 1978 in Salt Lake City the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL) committed to an effort to obtain “redress” for the wrongful incarceration during World War II of all Japanese Americans living in the western United States. Upon the recommendation of Senator Daniel K. Inouye and other Japanese Americans in the U.S. Congress, the route chosen was a Commission to investigate the circumstances surrounding the events of evacuation and internment. The late Judge William Marutani was the only Commission member who had experienced the events being investigated. The Commission determined that the evacuation and internment were due to racial discrimination and war hysteria and led to legislation introduced in Congress for an apology and compensation to Japanese Americans. The ten-year lobbying effort, led by Japanese Americans legislators in the Senate and House, was coordinated by Medford Leas resident Grayce Uyehara, who spent part of the week in Washington, D.C., volunteering her time.

The final touch was administered by then Governor of New Jersey, Tom Kean, who reminded a reluctant President Ronald Reagan of his own words, that “blood spilled on the battlefield is all one color.”

President Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, which offered the nation’s apology for wrongful incarceration and authorized the payment of $20,000 to each person who was forced to leave home pursuant to Executive Order 9066, and who was living when President Reagan signed the bill into law.

Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.

George Santayana, Spanish American philosopher

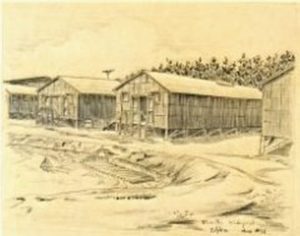

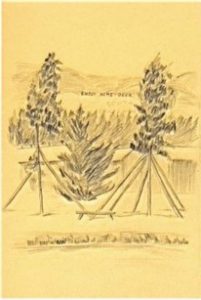

The originals of these three 1942 pencil sketches by Sumi are archived at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania’s Ethnic Studies Collection. That organization provided large (2 MB tif files) electronic scans which Sumi printed for the Medford Leas exhibit. Sumi has donated her personal papers from 1941 to 1989 to the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

Suye Kobayashi

photos from the collection of Sumiko Kobayashi

Two evacuation photos by Clem Albers

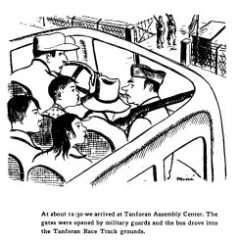

Miné Okubo and Citizen 13660

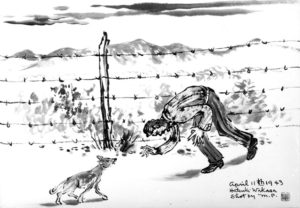

Citizen 13660 is a documentary in drawings and text on experiences at Tanforan Assembly Center and Topaz Relocation Center. Published in 1946, and still in print, it contains 200 of the approximately 2000 sketches that Okubo made of her experiences.

Google Books has a preview of the book with the first 45 pages including the captions. The Japanese American National Museum holds 197 of the original drawings but without the captions that add so much to the book.

These are the four pages that were displayed at Medford Leas. Click on an image to open the page about that image from the museum.

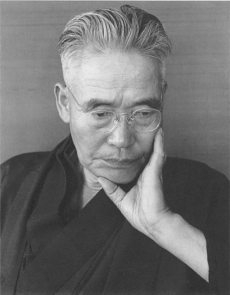

Chiura Obata and Topaz Moon

Except for during his internment, Obata was a faculty member in the Art Department of the University of California, Berkeley from 1932 to 1953. Obata biography. He initiated art classes at Tanforan Assembly Center and Topaz Relocation Center. Because of that cooperation with authorities he was so badly beaten by other inmates at Topaz that he and his family were released to Salt Lake City for their safety. The Medford Leas exhibit showed a photograph of Obata and three illustrations from Topaz Moon. Sumi (also spelled Sumi-e) is the Japanese name for Ink and Wash Painting.

27 Topaz Moon images,

Smithsonian “A More Perfect Union” collection

From the Smithsonian

National Museum of American History site:

A More Perfect Union –

Japanese Americans and the U.S. Constitution

NB: One can search the entire collection by location, photographer, etc.

Google preview –

Topaz Moon: Chiura Obata’s Art of the Internment

Sumi Kobayashi’s Sketches

The originals of these three 1942 pencil sketches by Sumi are archived at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania’s Ethnic Studies Collection. That organization provided large (2 MB tif files) electronic scans which Sumi printed for the Medford Leas exhibit. Sumi has donated her personal papers from 1941 to 1989 to the Historical Society of Pennsylvania. That site has a rather extensive biographical note about Sumi.

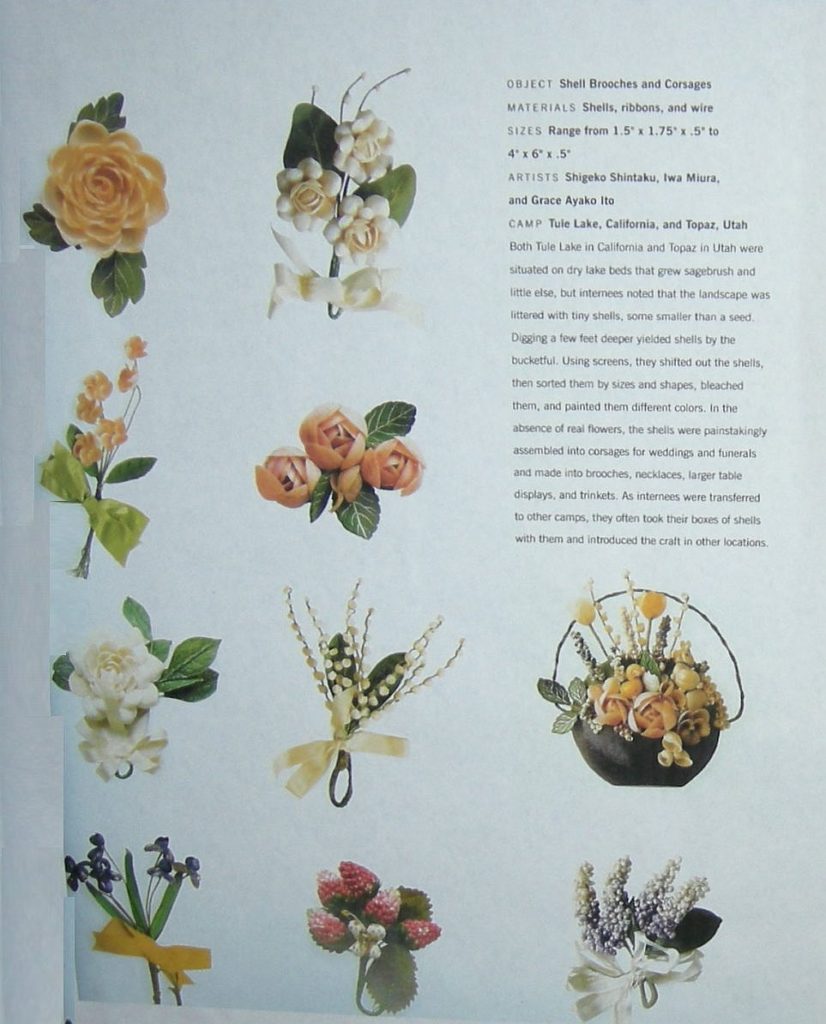

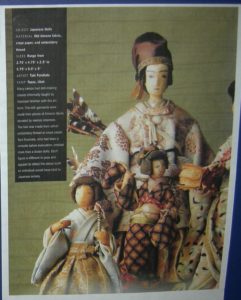

Evacuees sought to bring beauty to their bleak surroundings. These images are from The Art of Gaman: Arts and Crafts from the Japanese Interment Camps 1942-1946 by Delphine Hirasuna. “Gaman” is Endurance, Perseverence, Patience. The Tule Lake and Topaz camps were on ancient lake beds. The page on the left shows jewelry and other artifacts that were fashioned from shells picked up around the camps. Doll making was a traditional craft practiced in the camps from materials at hand. The text on these two pages gives detail on the materials used and the construction of the jewelry and dolls.

Delphine Hirasuna curated an exhibition of interment camp art at Smithsonian’s Renwick Gallery in 2010. There is a video of her describing the exhibition.

Dorothea Lange and Mitsuye Endo

Dorothea Lange became a well-known photographer in the 1930s with her images of displaced migrant workers. In the 1940s she photographed displaced Japanese Americans. Most of those images did not become known until 2006 with the publication of Impounded: Dorothea Lange and the Censored Images of Japanese American Internment. This fascinating 2006 NY Times article reports on the publication of Impounded and includes the Mr. Konda photograph and two more of the 800 that had been kept in the National Archives for decades. National Park Service’s website of the Manzanar Historic site includes four photo galleries: Ansel Adams, Dorothea Lange, Clem Albers, and Francis Stewart. However none of the 21 Lange photos on the NPS site show the grim conditions that caused most of her photographs to be impounded.

Adams, Lange, Albers, and Toya Mikataki are the photographers featured in Illusive Truth: Four Photographers at Manzanar by Gerald Robinson. Google Books previews Illusive Truth. Mikataki was an internee and his son, also and internee, wrote the introduction to Illustive Truth.

Mitsuye Endo challenged the right of the U.S. Government to hold her, a loyal American citizen with a brother in the U.S. Army, in an internment camp. Her attorney James Purcell filed a write of habeas corpus on her behalf. Unlike the other three internment cases, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in her favor in December 1944: she was free to leave. You can read more about her case here.

From the National Archives

—photographer Clem Albers

About the image

—photographer Clem Albers

About the image

photo at Topaz Museum

The View From Within

Japanese American Art from

the Internment Camps 1942-1946

In the fall of 1992, UCLA marked the 50-year anniversary of the Japanese American internment with a major art exhibit, “The View From Within.”

This painting was the cover illustration for the catalog of that exhibit.