Low

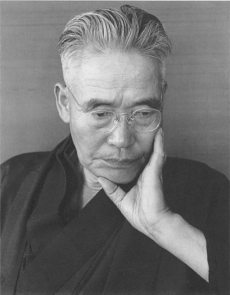

Vision Help -- How to Change Font Size Part One: Celebrating the Life of Tak Moriuchi Part Two: Imprisoned Without Trial |

||||||||||

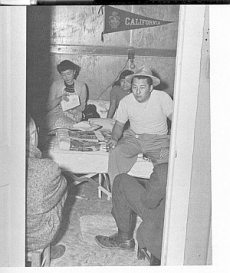

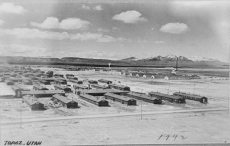

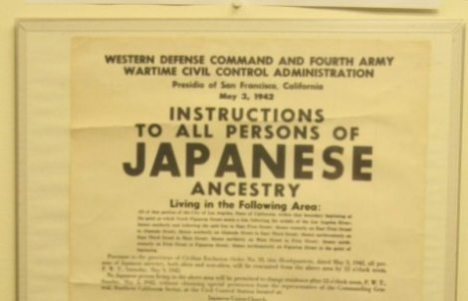

In October 2008, as part of the celebration of Tak Moriuchi's life, Sumiko "Sumi" Kobayashi prepared a display in the Medford Leas Gallery called "Imprisoned Without Trial." Every photograph and illustration on this page is from the exhibit. This Internet version adds depth by providing more information about the images and links to relevant Internet resources.

Eighteen current and former Japanese Amercan residents at Medford Leas (about residents) came to the east coast as a result of the United States Government placing all west coast persons of Japanese ancestry in American-style concentration camps. Most who moved here became residents because Tak Moriuchi convinced fellow members of the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL) that Medford Leas was where they wanted to be when their children had flown the nest and they faced possible health problems in their senior years. Suye

Kobayashi

Left:

Sumi's mother, Suye Kobayashi, at her 100th birthday celebration

at Medford Leas in December 2000. The two insets are from

the photos at right: Above: Wedding of Suye and Susumu Kobayashi,

July 19, 1922 in Matsue Japan; Below: Block 30 Kitchen Helpers,

Topaz 1945. Suye Kobayashi is in the center, wearing a white

cap.

Two evacuation photos by Clem Albers |

||||||||||

|

about photo ....enlarge photo |

|||||||||

Right:

In eloquent protest, a veteran of service with the U.S. Navy in World

War I wore uniform and decorations on the day he was evacuated.

27

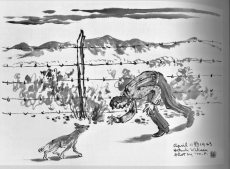

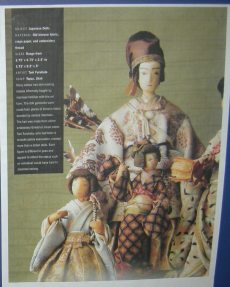

Topaz Moon images, Smithsonian "A More Perfect Union"

collection Google preview - Topaz Moon: Chiura Obata's Art of the Internment |

||||||||||

|

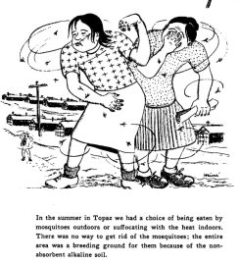

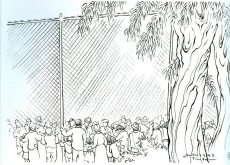

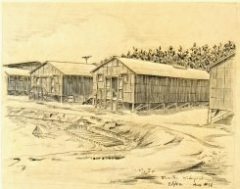

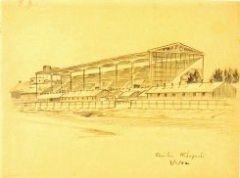

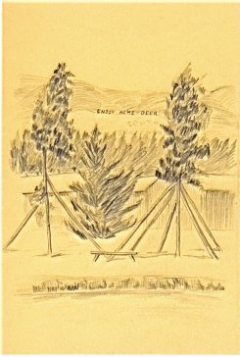

Sumi Kobayashi's sketches: |

||||||||||

Dorothea

Lange and Mitsuye Endo |

||||||||||

|

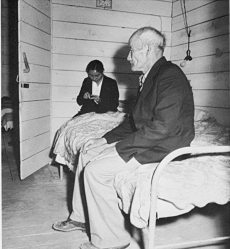

Old

Mr. Konda and Daughter in Converted Stable at Tanforan Assembly

Center |

|

|||||||||

Adams, Lange, Albers, and Toya Mikataki are the photographers featured in Illusive Truth: Four Photographers at Manzanar by Gerald Robinson. Google Books previews Illusive Truth. Mikataki was an internee and his son, also and internee, wrote the introduction to Illustive Truth . * * * * * Mitsuye Endo challenged the right of the U.S. Government to hold her, a loyal American citizen with a brother in the U.S. Army, in an internment camp. Her attorney James Purcell filed a write of habeas corpus on her behalf. Unlike the other three internment cases, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in her favor in December 1944: she was free to leave. photo credit: Obituary Chicago Tribune 2006. Shortly after her death the "Is That Legal?" site published an article by Greg Robinson, "Mitsuye Endo: Great in Her Obscurity" and one with a photo by Patrick Gudridge, "Honoring Misuye Endo: Rembering Her Case." |

||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

From

the National Archives |

||||||||||

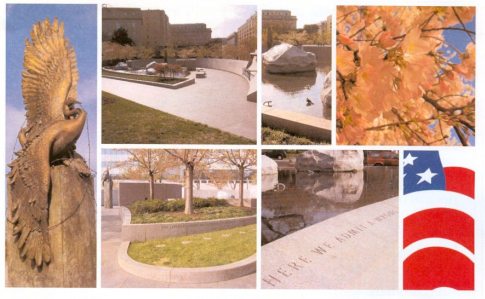

1992

photo of the Okuras who used their redress payments to establish

a foundation for mental health policy. |

|

|||||||||

|

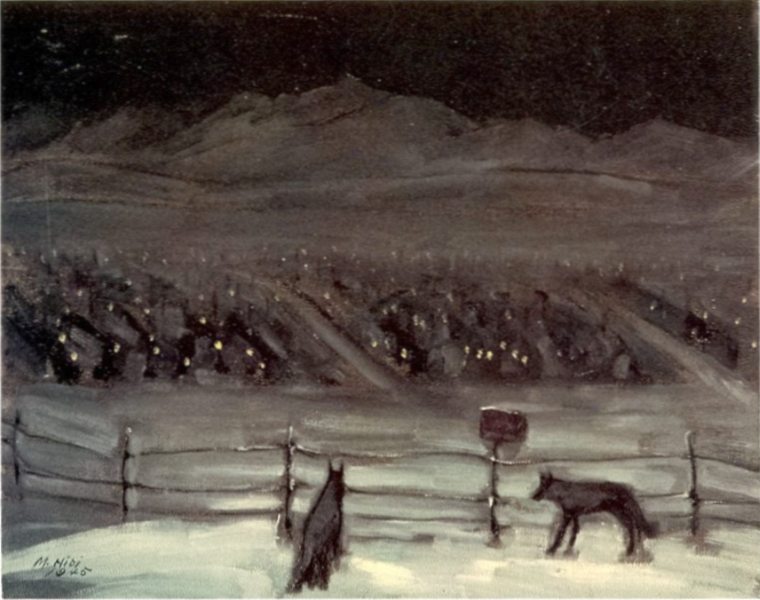

In the fall of 1992, UCLA marked the 50-year anniversary of the Japanese American internment with a major art exhibit, "The View From Within." The painting below, "Topaz WRA Camp at Night, 1945," by George Matsusaburo Hibi was the cover illustration for the catalog of that exhibit. Although there is no online preview of the catalog, the UCLA website provides online the companion 33-minute video "The View from Within." There is a choice of versions depending upon the speed of the viewer's modem.

I

downloaded and watched this video

through Realplayer and was enthralled. |

||||||||||

Imprisoned

Without Trial December

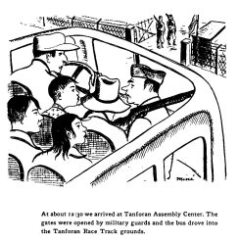

7, 1941 On the day after the attack the FBI and local police visited the homes and businesses of Japanese families, looking for contraband items like guns, cameras, short-wave radios, and took into custody community leaders: the leaders of Kenjin-kai (mutual self-help societies), Buddhist priests, and Japanese language teachers. It was literally the dreaded knock on the door at night. One of those taken away from their families was my father’s employer, a successful rose and carnation grower in San Leandro, California. For a long time his family did not know where he had been taken and when they would see him again. Fortunately he had a young adult son who was able to carry on the business until he leased the nursery and voluntarily evacuated his family away from the west coast. In the absence of martial law Japanese were placed under a curfew, 8 pm to 6 am, their assets were frozen, and travel beyond a radius of five miles required written permission from a U.S. attorney. In the 2-1/2 months after December 7 the Japanese communities waited apprehensively as Japanese military successes in Asia fueled fears of an attack on the mainland of the United States. Finally their uncertainty was resolved when President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 (EO) on February 19, 1942, which gave the U.S. Army blanket authority to move civilians out of the Western Defense Command. The EO makes no mention of “Japanese” but everyone knew it was intended to apply only to Japanese, aliens and “non-aliens” (citizens) alike, while German and Italian aliens were given individual hearings. Two arguments put forth for evacuation were that it was not possible to tell the loyal from the disloyal, and that the Japanese were removed for their own protection. The main argument given was “military necessity.” The Army’s Wartime Civil Control Administration (WCCA) organized the removal of all Japanese from Washington State, Oregon, California and the southern third of Arizona. Infants to seniors, immigrant aliens and American-born citizens alike, were taken to temporary assembly centers (map) at horse racing tracks hastily converted to living quarters, and fairgrounds—existing facilities able to house and feed a large number of people. Evacuees were assigned a family number (example 21518) and instructed to bring with them only what they could carry in their two hands. Everything else had to be sold at distress prices or placed in government warehouses. Pets had to be left behind. Families were picked up by the Army at designated points and taken in buses guarded by soldiers armed with rifles and fixed bayonets to assembly centers. The centers were guarded by armed soldiers around the clock, and visitors had to speak to their friends through a 15-foot high fence. Two-thirds of the evacuees were American citizens. The average age of those evacuated was 18.

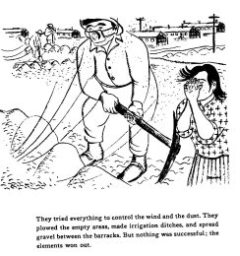

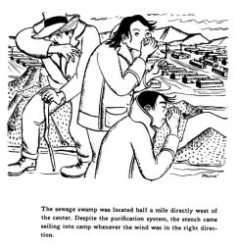

While the Japanese families were held in assembly centers, ten semi-permanent relocation centers (map) were being built on government-owned land; some were on Indian reservations. They were in eastern California, Idaho, Wyoming, Colorado, Utah, Arizona and Arkansas, each designed to hold 8,000 to 10,000 individuals in barrack cities. After the initial evacuation phase the job of running the detention centers was turned over to a civilian agency, the War Relocation Authority (WRA). One of the first casualties of evacuation was individual and family privacy. Life in the relocation centers was communal. In residential blocks 12 barracks surrounded a central mess hall and laundry/bathroom building. The 12 barracks for sleeping were divided into apartments of different sizes for different size families, one room to a family. Another casualty was parental control over their children as young people congregated in peer groups. Some young men went to more than one mess hall to eat meals. Each camp had

a hospital, high school, several elementary and nursery schools

and Protestant, Catholic and Buddhist churches. Each camp had a

Project Director with a Caucasian staff, who lived in their own

compound, but the bulk of running a “city” of 8,000

to 10,000 persons fell to the evacuees themselves. Within the confines of the barbed wire residents attempted to duplicate the community they had left behind. Besides performing the day-to-day tasks of running the camp, the evacuees organized classes for arts and crafts, poetry, and other hobbies, ran talent shows, held dances for the young people, showed current movies in the recreation halls, and organized baseball, football and basketball teams which later played local high schools. Every camp had a mimeographed daily newsletter and sometimes a literary magazine.

Pursuant to

their Quaker values the Society of Friends was one of the few groups

that sought to help the evacuees. The American Friends Service Committee

send layettes to all the camps for mothers of newborns.

One of the mothers who received such a layette is Florence Ishida,

a Medford Leas resident in Assisted Living. Quaker individuals

like Herbert Nicholson were loved by evacuees for bringing in items

that evacuees could not obtain themselves, to demonstrate that some

Caucasians had faith in them. Others followed

as employment opportunities opened up. John Seabrook, the “Henry

Ford of Agriculture” pioneered the frozen food industry in

South Jersey. He had contracts with the armed forces to supply frozen

vegetables, but because of the draft, enlistments and war industries,

labor was in short supply. He sent recruiters to all the camps,

inviting them to work at Seabrook with a promise of employment and

housing. A scouting team from the Jerome Relocation Center visited

Seabrook and reported favorably on the offer. Soon a stream of evacuees

from all the centers arrived at the small town in rural New Jersey.

Many children graduated from Bridgeton High School and went on to

colleges and careers elsewhere. Ellen Nakamura and John Fuyuume

established the Seabrook Educational and Cultural Center in Upper

Deerfield, NJ, which tells the story of the multicultural, multi-ethnic

“global village” that existed for a time in the area.

The

story of Seabrook is told in the 70th anniversary edition of the

New Yorker magazine, February 20-27, 1995.

The camps were emptied and the camps closed in 1945. The Japanese Americans tried to restart their lives, putting the painful past behind them. Many never told their children where they had spent the war years. The children often learned of their families’ past when they learned about internment in school and asked their parents about it. Growing up with the civil rights movement, the younger generation led the way in demanding justice for the violation of their parents’ constitutional rights. The first of the ten amendments to the Constitution of the United States known as the Bill of Rights reads: “Congress

shall make no law respecting an establishment of At its national convention in 1978 in Salt Lake City the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL) committed to an effort to obtain “redress” for the wrongful incarceration during World War II of all Japanese Americans living in the western United States. Upon the recommendation of Senator Daniel K. Inouye and other Japanese Americans in the U.S. Congress, the route chosen was a Commission to investigate the circumstances surrounding the events of evacuation and internment. The late Judge William Marutani was the only Commission member who had experienced the events being investigated. The Commission determined that the evacuation and internment were due to racial discrimination and war hysteria and led to legislation introduced in Congress for an apology and compensation to Japanese Americans. The ten-year lobbying effort, led by Japanese Americans legislators in the Senate and House, was coordinated by Medford Leas resident Grayce Uyehara, who spent part of the week in Washington, D.C., volunteering her time. The final touch was administered by then Governor of New Jersey, Tom Kean, who reminded a reluctant President Ronald Reagan of his own words, that “blood spilled on the battlefield is all one color.”

President Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, which offered the nation’s apology for wrongful incarceration and authorized the payment of $20,000 to each person who was forced to leave home pursuant to Executive Order 9066, and who was living when President Reagan signed the bill into law.

|

||||||||||