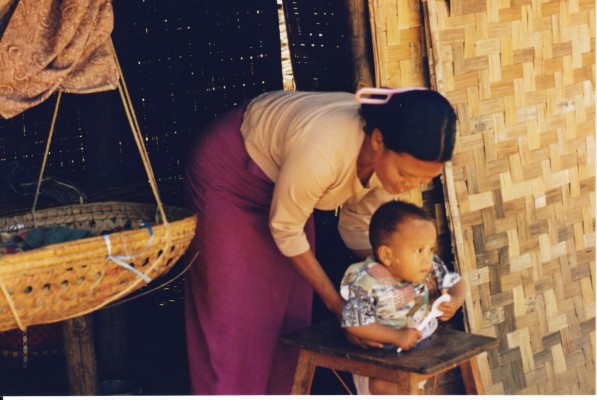

Mother preparing

meal for child, Cradle swing at the left

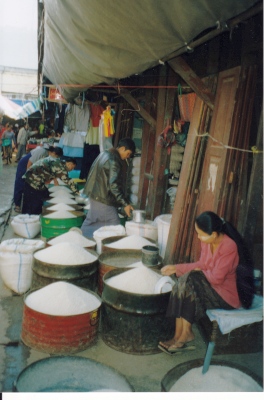

Varieties

of Rice

ow HOME MLRA

Myanmar

in Transition |

|

Each year, Medford Leas participates in the Great Decisions Program. of the Foreign Policy Association (FPA). In 2013, in addition to the briefing book, a half-hour PBS documentary was provided for each of the eight foreign policy topics. One of the eight topics this year was: Myanmar and Southeast Asia. The PBS documentary for Myanmar was called The Generals and the Democrat -- Burma in Transition. That link goes to a one-minute trailer for the documentary, which can be purchased from iTunes for $2.99. |

At Medford Leas the Myanmar/Burma program included 1) a handout with background information and a timeline, 2) a presentation "Burma and Early Independence" by Helen Vukasin, a resident who lived in Burma from 1951 to 1953, 3) the 30-minute PBS documentary and 4) a presentation "Reasons for Optimism about the Future of Burma" by Beth Bogie, a resident who has served as newsletter editor for the Cetana Educational Foundation and as a mentor for Burmese students in the United States. During the winter and spring of 2013 Ms. Bogie's photographs of Burma/Myanmar were on display in the Medford Leas Residents Art Gallery. They were taken on three separate trips to Burma between 1999 and 2003. |

|

|

|

|

Americans have been in residence in Burma since July 1813. In that year Adoniram and Ann Judson, Baptist missionaries arrived in Burma. Their focus remained primarily on education down through the years. They contributed much to the US understanding of the Burmans and other ethnic peoples that inhabit this small but resource-rich arable country. However, Burma remained almost unknown to most Americans until WW II when hundreds of American soldiers were sent to retrieve Burma from the Japanese Occupation.

The Burmese have a centuries-long history of independence. As early as the middle of the eleventh century under the Pagan dynasty and later in 1485 under the Toungoo Dynasty the Burmese unified with smaller ethnic groups and resisted outside invasion. Down to the very last of the Burmese Dynasties, the Burmese insisted that foreigners observe the Burmese culture and mores especially with respect to formalities related to the Kings of Burma. Ultimately, the rise in wealth and power of the British East India Company, originally chartered by Elizabeth I, overwhelmed the competition of Portugal, Spain and France in Southeast Asia. Bit by bit, the British occupied Burma as part of the Indian Empire through wars in 1824 -25 and 1852-53 until it finally annexed the last of the now land locked empire under the last King of Burma, Thibaw, in 1885. From this time till after WW II Burma was ruled by whomever was appointed by the Viceroy of India. The conflict among the ethnic groups has roots in cultures, language, religion and geographic isolation. The predominant group is Burman. Other ethnic groups are, the Karen, the Kachin, the Shan, the Chin and the Mon. They include Buddhists, Muslims, Hindus, and Christians. This diversity remains a problem to this day as the ethnic groups have wanted autonomy. Some have even wanted complete independence and so they resist nationalism and unity. |

•

January 1947 - Great Britain agreed to give Burma independence, along

with India, .after negotiations with Thakin Aung San. (Thakin was the

name taken by the anti-colonial group headed by Aung San in the forties.

The group originally supported the Japanese and were militarily trained

by them. However, they soon saw the brutality of the Japanese and joined

sides with the British in the War.)

hlv 2/28/13 |

|

BURMA

IN EARLY INDEPENDENCE Burrna has been very important in American Foreign Policy since 1948 when India and Burma got their independence from the British Empire. I was fortunate enough to spend two years in Burma (1951-53). My husband was part of a team of economists under Robert Nathan working with the Ministry of Planning to create a 5- year economic plan. I spent my time working on a Master’s thesis about the development of the Irrawaddy delta as the rice bowl of SE Asia, studying Burmese dance and teaching English in a Burmese school. We were in Burma on a project which was primarily funded by US foreign AID and connected to a large scale engineering program for an airport and other infrastructure projects. In addition, there was a major AID Mission, of the post war Economic Cooperation Administration, supporting dozens of development projects all around the country. Just to place Burma and India in the important role they played at this time in history. Before WW II there were no so-called developing countries. All such countries were still in a colonial status. Burma and India were the first to achieve independence and remained the only ones until the Gold Coast, in Africa, won independence as Ghana in 1957, 9 years later. It was

a new and unique situation in world politics. |

|

|

|

The US reached out to help and support a country dedicated to parliamentary democracy. It was not easy. The local ethnic groups did not want to be under the yoke of the Burman’s no matter how democratic they seemed to be. During this period there were at least 2 factions of communists (White Flag and Red Flag) in the countryside plus ethnic groups such as the Karen, the Shan and the Kachin seeking independence or at least autonomy. And on top of that the Chinese nationalists, the Kuomintang under Chiang Kai-shek were bivouacked in Burma along the Chinese and Thai borders, making incursions into Communist China or being chased by the troops of Mao Tse Tung -- and also fighting the Burmese nationalist troops. This latter led to an interesting event. It was one of those strange US policies that give the US a bad name. It was a shock to Americans both in Burma and abroad. The KMT (Chiang Kai-shek) troops were inside Burma along the Thai border; the Burmese army, 14,000 strong, were sent to get them out. So there were the KMT troops with US support and US weapons killing Burmese soldiers. Meanwhile down in Rangoon, the US was supporting a very large aid program. The Burmese President sent an ultimatum to Washington to cut off support of the KMT. Secretary of State Dulles refused. This was too much of a contradiction for the Burmese. Early one Sunday morning when we opened the government newspaper – in a surprise attack - the Burmese government announced that the American Aid Program was asked to leave the country. And three months later they were gone. It was the beginning of a period of back and forth relations between Burma and the US. The Cold War led both sides (the US and the USSR) to competitive pressures to achieve influence in various areas and especially Southeast Asia. |

|

Still this was 1952, a period of hope. India and Burma while professing independent socialist leanings were not willing to be drawn into the Cold War. India and Burma formed a liaison with Yugoslavia at the time when that country was separating itself from the USSR. These three major developing countries met in India at a Conference and affirmed their democratic socialist beliefs and their determination for neutrality in the Cold War. They declared themselves countries of the Third World. In the meantime, the US was negotiating to return to their aid projects in Burma. Burma stood firm against the issue of US support of Chian Kai-shek and ultimately, several years later, they won the case. They also stood firm on their declaration that they did not want out-right aid that might have strings. They preferred cooperation or loans from the benefactors. And over the years there were many vying for favor from resource-rich Burma, including the USSR, China, Israel, Yugoslavia and others. We left Burma in 1953 at the end of our two year contract. At that time PYIDAWTHA (the eight year Economic Plan which means Towards a Welfare State , a concept conceived of by Thakin Aung San in the 1940s) was on the edge of a cliff. With the end of the Korean war which supported an elevated world price of rice, the price nose-dived. It was the high price of rice on which the whole plan was predicated. Over the next few years the plan retreated to a four year plan and more modest goals. So I have given you a snatch of what Burma was like in the post colonial days. What happened to American Burmese relations in the years between1953 and what we all hope is a move toward parliamentary democracy is complicated and with enough information for a whole session of Great Decisions. We hope the handout you received provides enough highlights along with the book and the DVD to bring you up to date. |

As you will see

in the DVD we are about to show, Burma has stood still in many ways

during the remaining years of the 20th century. Following the video, Beth Bogie, our resident authority on the latest news from Burma will give us her thoughts on the present and future. Now the video! If

the embedded trailer for the video doesn't work for you, |

|

Good morning. I’m going to augment the DVD with some reasons for optimism about the future of Burma and the reform movement. But first, how were the planets so aligned as to produce the amazing shift from hard-line dictatorship to a democratic reform movement. Diplomatic efforts were mostly ignored. Here’s what weighed more heavily:

|

|

|

|

Is the reform movement sustainable and do the Burmese people have enough experience with democracy to make it work into the future? The military hard-liners can constitutionally take back the reforms at any time. The election in 2010 was a sham, with 25% of seats reserved for the military and 80% of the remainder for military supporters. As the New York Times put it: the generals just put on civilian clothes. Suu Kyi and her National League for Democracy refused to participate. Despite uncertainties about the military, the reforms have been dramatic and positive, such as: releasing Aung San Suu Kyi and recognizing her opposition party, releasing many political prisoners, ending censorship and lifting restrictions on the Internet, reducing taxes and rewriting laws on taxation and property ownership, and much, much more. The genie is out of the bottle and will be difficult to put back in, especially since the walls of isolation have fallen. Governments and the media are finally watching developments with an eye to future investment, which Burma sorely needs. And what of the Burmese people? They have struggled mightily against their oppressors, both British and Burmese military. In 1947, General Aung San, father of Aung San Suu Kyi, won independence for Burma from the British. Under the British, Burma was treated as a province of India. The Burmese would have become acquainted with the Constitution of the British Indian Empire, as the DVD indicated. Democratic principles and processes would have been embedded in that document. Between 1948 and l962 Burma was independent and a democracy. The assassination in 1947 of soon-to-be-President Aung San and his cabinet was a severe setback, but the democracy moved forward under President U Nu. Self-governing organizations of a civil society were growing and a reflection of a free country, however much it was in a state of turbulence, as described by Helen. By way of background, in the first half of the 1900’s before World War II and in the decade after that, Burma was a relatively prosperous country. Burma was the rice bowl of Southeast Asia. It was considered one of the Asian Tigers, like Taiwan and South Korea. Education in this period was one of the highest values, and medical education was at the top. Burmese doctors were considered the best in Asia. Not only were there the British vernacular schools; there were also 550 American-style high schools established by American missionaries, with teachers from all backgrounds. A Burmese woman in her 80s living on Long Island near my former home told me proudly, “We had everything you had.” She added quietly, “We forgot out roots.” I believe that the British ill-treatment of the Burmese, favoring Indians over Burmese for the Burmese civil service, for example, was probably mitigated to a degree by the democratic attitudes of the teaching and medical missionaries from the U.S. One American professor of botany at the University of Rangoon (Yangon), when he returned in the late l980s to Burma, in a small opening for visitors, he was greeted by one thousand of his students. He had taught them from l930 to 1966, when he was the last missionary to leave Burma. In l962, General Ne Win took over the government in a coup, beginning the 50 years of isolation under military dictatorship, when borders were shut down and all foreigners and foreign investment were kicked out. The economy did a nosedive. Soviet-style socialism, nationalism, superstition and paranoia ruled General Ne Win and the military. Did the Burmese sit on their hands? Certainly their tenacity, their quiet resistance, their resilience, and their sense of humor were sources of their survival. I observed firsthand from l999 to 2010 their struggle under the military junta, and their unfailing warmth and hospitality. In l988, however, explosive tensions erupted. Students led a national uprising in the name of democracy. That, in my opinion, was the Burmese Spring, no different than today’s Arab Spring. Some 3,000 students were killed by the military, hundreds fled through the jungle to refugee camps in Thailand, and hundreds more were imprisoned. Many were released from prison only recently. That same year Aung San Suu Kyi returned to Burma from England to care for her dying mother. People asked her to lead a democracy movement, and she formed a party called the National League for Democracy. In a national election called by the military, her party won 59 percent of the vote and 81 percent of the seats in Parliament. The election was promptly annulled by the military. She was already under house arrest, which continued off and mostly on for the next 15 of 21 years, and many members of her party were imprisoned. Her belief in non-violent resistance in the name of democracy carried her through to her release in November 2011. In by-elections in 2012, she and her party members won 43 of 45 available seats in the lower house of Parliament. She has written two books on democracy and has often spoken to the Burmese public on the subject, such as when attempting to rebuild her party in 2002. She has famously said, “It is not power that corrupts, but fear. Fear of losing power corrupts those who wield it, and fear of the scourge of power corrupts those who are subject to it.” |

| After the1988 riots were put down, fear did grip the people. But in 2007, Buddhist monks took to the streets in protest of higher fuel prices. Soon they were marching in support of human rights. We looked on at our televisions with our hearts in our mouths. Within a few days of protest, many of the monks were dragged out of their homes at night and murdered by the military. This “Saffron Revolution,” so named for the color of the monks’ robes, was the first protest in Burma witnessed by the outside world. It was possible because of technology heretofore largely unavailable to the average Burmese –the Internet, digital cameras. Now pictures could get out.

During the years leading up to the protest, “The Democratic Voice of Burma” was beaming broadcasts about democracy from the U.S., in the Burmese language, through a server in Norway to the people of Burma, who would listen on their radios. This avoided the government-operated server in Burma, whose use was heavily restricted and monitored by the military. At the time of the monks’ protest, the “Democratic Voice of Burma” was said to have had a major impact on the broad public.

Public support for democracy is alive and well in Burma. I don’t see the reform movement simply as a top-down phenomenon, without any role having been played by the people, and only to be taken away when the military chooses. Democratic reforms are growing roots. And the gentle Burmese people are finding their voice, as in the case of the hydroelectric project and in voting for 43 of the seats for the democracy candidates. It will be interesting to see what general elections will bring in 2015 . It’s important to remember that for 50 years you did not read about the brutal repression going on in Burma. You didn’t read about Burma at all. Now that the international media has access to Burma, you are hearing not only about the reforms, but also, for the first time, instances of strife. It’s important to keep this in perspective.

The strife with the ethnic

states surrounding Burma is in part the legacy of colonialism. When the

British finally took over the entire country in l885, they controlled

the Burmese, the largest ethnic group in the central, flat part of the

country, while leaving alone the 135 ethnic peoples residing in surrounding

mountainous areas who were too hard to subdue. This bred resentment between

the Burmese and the ethnic states and resulted in the formation of an

army in each ethnic area with an intent to secede or at least to protect

themselves. Frequently the military burned down villages in the ethnic

areas, took people into forced labor and raped the women. Today, under

President Thein Sein ceasefire agreements have been reached with all but

one ethnic group and the latter is being negotiated. I believe that the

reforms and a more democratic environment will ultimately quench the desire

for separation from the Union of Burma. |

|

|

Suset on the Irrawaddy |

What of the military? Yes, it is a wild card, but little has been reported on this issue, except concern. The key to a sustained democracy may lie with finding a role for the military within a democracy. I learned that from a very bright Burmese civilian, Tin Maung Than, who had a graduate degree from the Harvard School of Public Administration. On returning to Burma, he became editor of Thint Bawa, a journal about social issues. In 2001, Tin was forced to flee Burma with his family, first to Thailand, then to the U.S., where he received political asylum. Today he is back in Burma, as an advisor to President Thein Sein! The Burmese military may be fearful of being sidelined, Tin would say. It occupies a privileged place, as in so many developing countries, because the military threw off the yoke of colonialism. The public can’t forget that. If the government is to avoid further coups, the new president must find a way to put the military under civilian control, possibly the most difficult challenge of all. The need for foreign investment is crucial. As of August, President Thein Sein was moving forward with a focus on market reforms, after dealing first with political reforms. Measures are aimed at the U.S. and Europe, as well as the Association of South East Asian countries (ASEAN), South Korea and Japan, while reducing dependence on China. In July he reached an agreement with the Thai prime minister for construction of an economic zone and port, to be built by an Italian-Thai Development Corporation. The project includes a steel mill, petrochemical plant and oil refinery. Thein Sein and his cabinet have introduced pro-foreign investment measures, such as replacing a fixed exchange rate with a managed float, allowing some privatization of state enterprises in the fields of energy, health and education. A new investment law will provide for fully foreign-owned companies, and joint ventures with at least 35% foreign capital. It will allow foreigners to lease land and reaffirms existing protections against nationalization. The government will require all unskilled workers and a rising percent of skilled workers to be Burmese. This gets at the Chinese projects, which use primarily Chinese labor. Large delegations from the U.S. and U.K. have responded. G.E. has struck a deal to provide x-ray machines to two private hospitals and sees this as only the beginning of involvement in Burma. The Obama administration has lifted bans on investment in the state-owned Myanmar Oil and Gas Enterprise; and at a business forum in Cambodia last July, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton introduced Thein Sein to American corporate leaders. President Thein

Sein has also gone after Japan as a counter-balance to investment by

China. Two dozen Japanese engineers are drawing up a master plan to

remake the roads, telephone and Internet networks and water supply and

sewage systems of Yangon, the country’s long-neglected commercial

capital. The industrial zone will also include banks, schools, hospitals

and other city amenities. Thein Sein is requesting that the project

be finished before 2015, viewing the project as helping to win the next

election. During the past decade when the West imposed sanctions on Burma, ASEAN pursued a policy of “constructive engagement,” a soft policy which notably wouldn’t interfere with trade with Burma. In 2006, when Burma was scheduled to become chair of ASEAN, member countries were so embarrassed by conditions in Burma that they advised Burma not to take the chair. But in 2011, based on the apparent “roadmap to democracy,” the ASEAN members approved Burma’s taking the leadership role in 2014. There are many aspects of ASEAN activity that will be supportive of Burma’s reaching its economic goals. |

President Thein Sein is targeting a 1.7-fold increase in per capita Gross Domestic Product after the first five-year plan, which would seem to end in 2015.

He has four guiding principles:

• Agriculture and all-round development will be the top priority;

• Growth must be proportionate and balanced among all states and divisions;

• It has to be inclusive for the entire population;

• There must be improvement in the way statistics are collected.There is so much that bodes well for this infant government. No one can predict the future, but in my mind, it looks very promising.