|

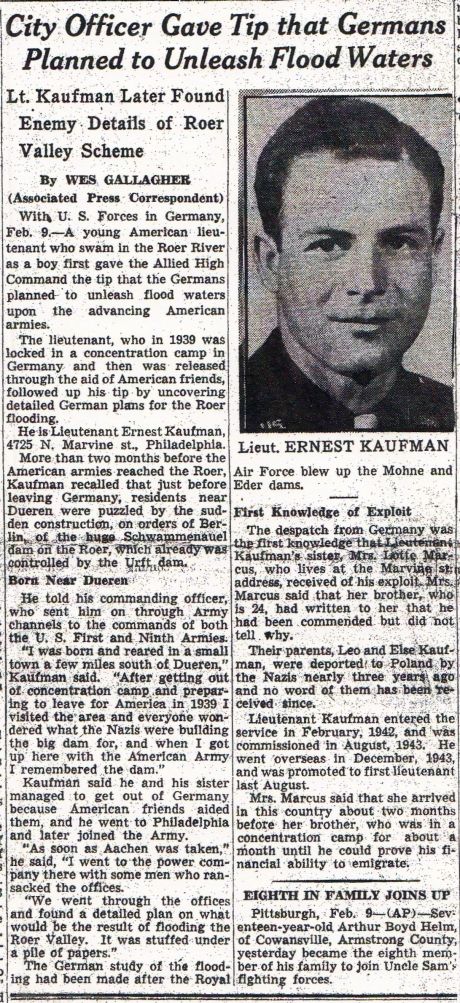

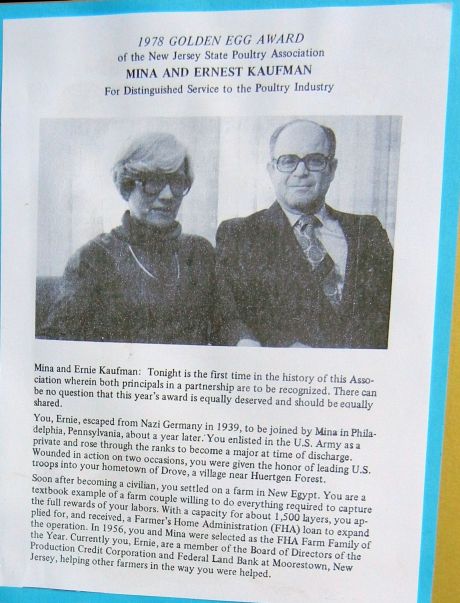

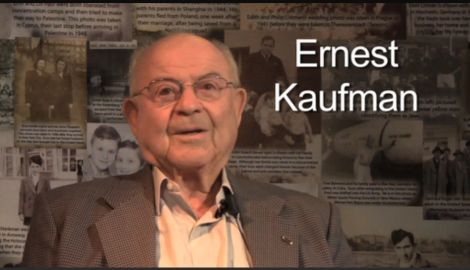

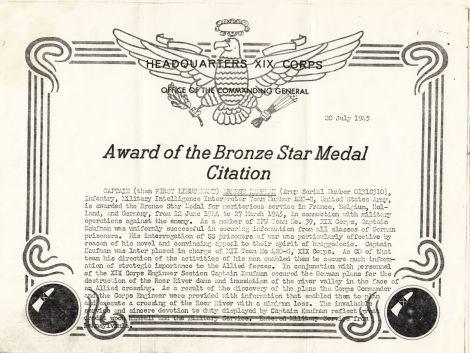

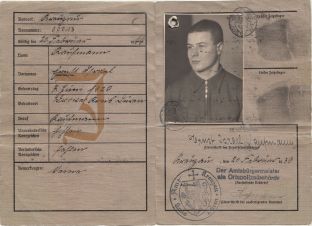

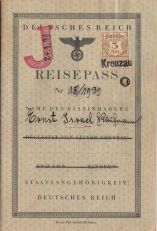

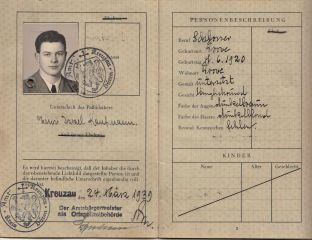

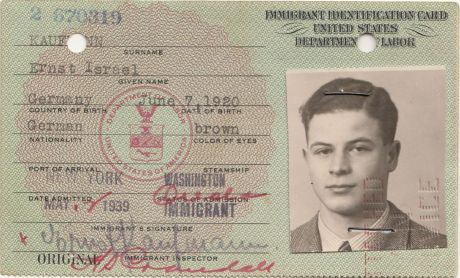

In 2014, at the age of 94, Ernest frequently speaks to veterans, civic groups, and school children about the Holocaust. Ernest gave his talk at Medford Leas on May 10, 2014. He has graciously provided mlra.org with the text of his speech (this column) and with photographs and documents to illustrate his story (right column). His is an unusual story. In 1938, the day after Kristallnacht, Kaufman was imprisoned in the Buchenwald concentration camp. He was released after four weeks and immigrated to the U.S in 1939. After Pearl Harbor, Kaufman enlisted in the US Army and served in Germany as an intelligence officer. In 1945 he received the Bronze Star Medal Citation for meritorious service. He stayed in the military until January, 1951. In 1978 Ernest and his wife Mina jointly won the 1978 Golden Egg Award of the New Jersey Poultry Association. He moved to Medford Leas in 2001. ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ "Holocaust

– Survivor or Escapee?” They say that

I am a Holocaust survivor. I had volunteered after Pearl Harbor and was serving in the American Army when mass – slaughter of German Jews began early in 1942, after the infamous Wannsee Conference that planned the so-called “Final Solution,” and ordered the systematic extermination of all Jews. Shortly after it, my parents and many of my relatives and friends were deported to somewhere in Poland, and murdered. They were being “resettled,” as our Christian neighbors had been told. Only a long time after the war did we find out that they had been taken to Belzec, a “Death Camp,” where the Nazis killed more than 500,000 people, men, women and children, in less than nine months’ time. THEY were VICTIMS of the Holocaust, and others at war’s end became Holocaust SURVIVORS, having survived the horrors of the death camps, while during that time I was actively engaged, though very indirectly and only in small measure, in trying to save them, having been lucky enough to emigrate before WW II, and thereby ESCAPE their tragic fate. Here is my story:I was born to Jewish parents shortly after WW I in a small town in Western Germany, a town in or near which according to existing records my family had been living since 1713, and most probably for much longer than 300 years. My father, a butcher, had spent four years in the German Army in WW I, fighting the Allies and the Americans on the Western Front. My mother had four brothers, all of whom fought in WW I, where one was killed in action, and a second one died after the war of injuries sustained in combat. My father was demobilized, a master sergeant, decorated with the Iron Cross. Shortly after he came back to the house he had built before he married my mother in 1914, my parents were forced to give up two rooms in their house to, and share the kitchen with, a French Officer and his wife. The Captain was in command of a Senegalese Foreign Legion company, Occupation Forces quartered in military barracks on the outskirts of our town. It might be interesting to note here that French military units occupied the entire German area west of the Rhine River until sometime in 1930, long after the end of WW I. When they left, the area was to remain demilitarized according to the Treaty of Versailles, and it stayed that way until Hitler in 1936 marched in with his military units, unopposed.

How different would the decade that followed have turned out if

the French had only sent, or threatened to send, a Military Force

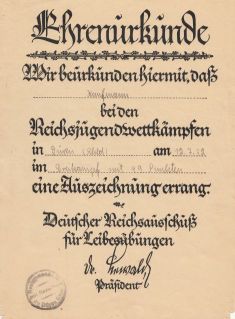

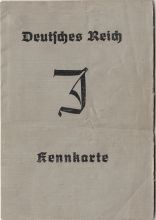

across the border to oppose his move! Our life, as I was told, and as much as I remember, was not easy, and typical of existence in a rural community. Everyone was struggling to overcome a terrible inflation in the early 1920’s, the aftermath of a lost war, and where a pound of butter would cost three marks one day, and three thousand the next. Economic conditions were bad, the Allies had forced Germany to pay huge reparations, unemployment was high, many people were hungry, and blaming the Communists and Democrats, and especially the Jews for all that was wrong, was what eventually got Hitler to power. By 1930, after four years in our local elementary school, I went to the gymnasium at Dueren, six miles away, enrolled in an academic curriculum and hoping to some day become a veterinarian. After Hitler came to power in 1933, and even until he marched into the Rhineland in 1935, we were spared the threats and physical attacks that Jews in other parts of Germany had already been subjected to for some time. When fellow students began joining the Hitler Youth and were ordered to avoid contact with Jewish classmates, some became abusive even to our non-Jewish classmates who stayed friendly with us. I must say that teachers, some of them soon coming to school wearing Brownshirt uniforms, were intimidating, but generally fair to us. In late 1935 we were told that after the end of the current school year no Jewish students would be permitted to attend classes at the gymnasium and other institutions of higher learning any more, and that is how my formal education came to an end before my 16th birthday. By that time emigration became a popular topic for us, even though most of our Christian neighbors and friends told us that this Nazi regime simply could or would not last much longer, and that we should just wait it out. But anti-Jewish edicts and actions became more severe and more frequent, and some of our friends and acquaintances who had the opportunity to leave for a country willing to take them, and that was always the big problem, left as soon as they were able to. For me it was trying to learn a trade or profession that would enable me to earn a living even if I should end up in a country whose language I did not speak. Beginning an apprenticeship with a Jewish firm that was still operating a large salvage yard near Essen, in the Ruhr area, I worked in the machinery repair shop for two years, until the firm was “aryanized” in 1938, and I was let go. While in Essen I had registered with the American Consulate at Stuttgart and received a number on the waiting list of the German quota for a visa to the States, a list existing or established because of the large number of applicants who hoped to go to this country after the Nazis came to power. Kristallnacht and Arrest For the next several months after coming home from Essen, I found mechanical work with Christian family friends in towns where no one knew I was Jewish, until on the morning of November 10th, 1938 I got a phone call from my sister, telling me to go home immediately, because, as she said to me, in English, “all the synagogues are burning.” – I got on my bike and headed for home, some 15 miles away, passing our burned out synagogue on my way. No sooner had I arrived at home that our local policeman, a neighbor and longtime customer of ours until my father was forced to close his shop, came and apologetically said that he had orders to arrest every Jewish male between the ages of 16 and 65 “for their own protection from the enraged German populace,” because a young Polish Jew had killed a German Consular Official in Paris. The policeman knew my father was not yet 65, said that he would disregard his orders, but I would have to go along. It was the only time I ever heard my father raise his voice, when he asked what ever for he spent four years in the trenches fighting for Germany, and what for his wife’s – my mother’s – two brothers gave their lives fighting for the Fatherland. - Our good neighbor of course had no answer for him, and off I went with him, to jail, a converted room in the local firehouse. PART

2 Chased off the train by SS-guards who used their rifle butts to hurry us along, we were loaded on trucks and hauled off to the Concentration Camp. Lined up for a roll call, our heads were shaved and then we were marched off to barracks that had bunks arranged in several layers, like shelving, each one about three feet above the next. It was November 13th, and having arrived with just the clothes on our backs that we lived in as long as we were in camp, lying close together on the bare boards kept us from freezing. Fed once daily, we were lined up in columns, and the first several rows of us were handed mess kits and spoons by so-called “other” camp prisoners who wore striped prison clothes, given a ladle full of some unidefntifiable slop and ordered to finish eating while standing in place. That done, the first group of men stepped aside, handing the mess kits and spoons, unwashed, to the next group of men that moved up, following the same procedure until all were fed. After that the utensils were washed, under supervision, because of the short supply of water we had, so short that it rarely gave us a chance to get washed during the entire time of our confinement. You can just imagine the degrading and unsanitary conditions that we had to live with. We of the “Kristallnacht” Action were lined up daily for roll call, and even though we were not made to work, some of the ill and elderly – in other parts of Germany the Nazis arrested many men much older than 65 – did not survive the harsh conditions and died. Walking around in our fenced-in compound I also met up with several cousins of mine who lived in other parts of Germany. Across the fence we watched the long term prisoners, those in the striped prison garb, line up mornings for formations, and then being marched off or driven off to work details. They came back in the evenings and were again lined up in formations for roll call and to watch punishment meted out. This was where the SS-guards tried to outdo each other in how much pain or punishment they could inflict. It was horrible to watch them hang people, or see them tie a man to a pole and flog him until he was unconscious, or tie a man’s hands behind his back and then hang him on what looked like meat hooks on a wall, cut down only after he had fainted, or worst of all, stick a man into a barrel spiked with nails, roll him down a hill and then let dogs finish him off. Every killed man’s family was routinely sent a container supposedly containing his ashes, always with the explanation that he was killed while trying to escape. Man’s inhumanity to man in action. Our families were told where we were, and that anyone who could show that he would leave Germany before long could be released from Concentration Camp. Not having any connections outside Germany, my desperate parents contacted a friend of mine who had earlier gone to this Country, the United States, and joined relatives who had been here for years. They told him of my predicament and asked if there was anything he could do, that I needed an “Affidavit of Support” to be released from Concentration Camp. My friend John spoke to the Couple he was rooming with, and without hesitation they themselves sent the required papers sponsoring me, a total stranger to them. They thereby guaranteed that I would not become a public liability for at least five years, the time it usually takes for an immigrant to become a US citizen. They saved my life, and I, and my family owed and showed them our gratitude as long as they lived. I was released from camp after almost 4 weeks, as was my brother-in-law who was helped with an affidavit by a distant relative of his, and we were both handed discharge certificates signed by Camp Commandant Koch, the husband of Ilse Koch, the infamous “Bitch of Buchenwald” who is said to have had lampshades made of human skin. Reporting as ordered to Gestapo Headquarters at Aachen on our return, and only after having been forced to even pay for the train fare to and from Weimar were we allowed to return to our homes. Coming back from Concentration Camp, we found out that the Nazis had ordered that, in order to pay “for the damages this Jew caused in Paris,” where that young Polish Jew had killed the German consular official, all German Jews had to pay 25 % of whatever they owned to pay for those so-called “damages.” Early in 1938 already all Jews living in Germany had been forced to submit a list of everything they owned, and were now assessed accordingly, forcing many to sell even their homes to comply with those draconian orders. It was always at ridiculous prices that the Nazis dictated. Every piece of jewelry and precious metal except plain wedding bands had to be turned in, exchanged for scrap value, a pittance that was again dictated by the Nazis. My parents had to sell a parcel of land we had used for pasture in the horse and buggy days, not to a neighbor who offered a decent price, but at a ridiculous price to the local mayor, a good party member. We had to give up our telephone, and our radio was confiscated – listening secretly to foreign short-wave stations, our only source of unbiased news, was gone after that. Listening to foreign radio stations by the way was forbidden also to all Germans. Our friends and neighbors were warned not to talk to us any more, let alone socialize with us. Actions to harass and isolate us continued, and life for all of us became more difficult every day. PART 3 I was fortunate to have a fairly low quota number on the American Consulate’s waiting list. I got an appointment to appear there in April 1939, and after a thorough physical and mental exam I went home, visa in hand. Two weeks later I was sailing for this Country aboard the United States Lines SS Washington after a tearful farewell from my parents – now alone since my sister and family had left for Philadelphia some weeks before. I got off the ship with four dollars in my pocket, the equivalent of ten marks that I was permitted to take with me. The Germans by that time had blocked the bank accounts of all Jews and controlled all withdrawals. Fortunately for me, they had still allowed my parents to pay for my passage out of our blocked account. At the pier in New York I was met by my friend John and Ann and Joe, my sponsors. They had found a family with which I would stay for some weeks, babysitting two young boys for room and board, and for the summer I would go to upstate New York as houseboy or handyman with a family that spent the summer vacationing on their farm. It turned out to be an excellent opportunity for me to learn to speak English. After the summer I moved to Philadelphia to live with my sister and family, and there I also soon met Mina, my wonderful wife. Many different jobs later, from being a helper on a delivery truck to sorting dirty rags, until I found a steady job as mechanic, building truck bodies for Bendix Aviation, a defense contractor. A good job, that got me an occupational deferment from the Draft. I had applied for it, because I was saving every penny I could while desperately trying to get my parents out of Germany, where life for them had become almost unbearable, and because by that time any passage out of Germany would have to be paid for with foreign currency. Then came Pearl

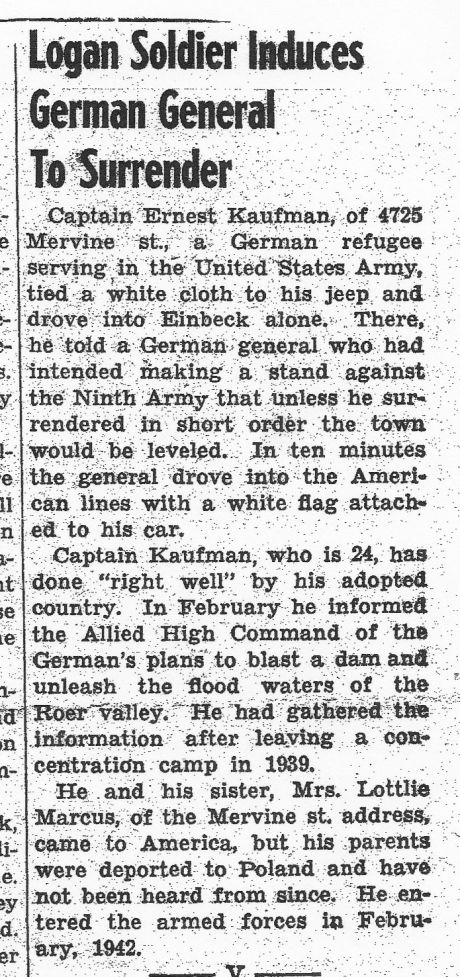

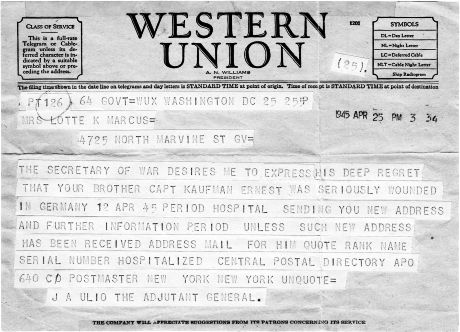

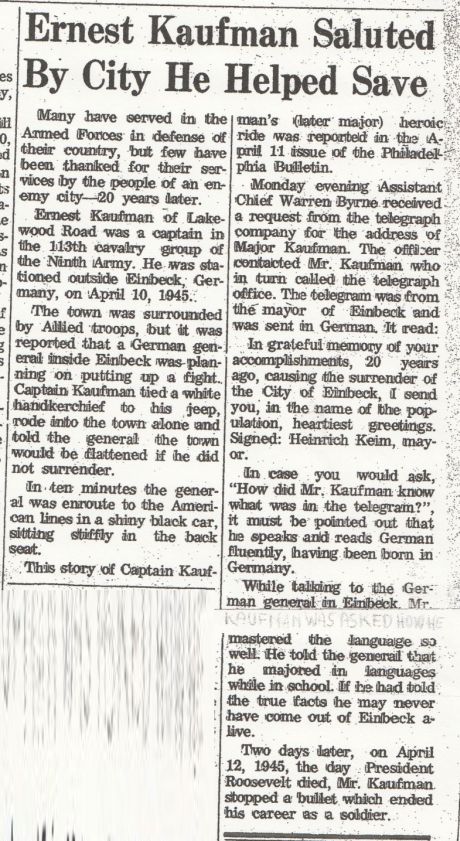

Harbor, and with it disappeared any chance to save my folks. When Congress in 1942 passed a law that anyone who for at least six months had served honorably in the Military could be naturalized without having to wait the usual five years before applying for citizenship, I made use of the opportunity, filed the necessary papers, and in October I was naturalized in Boston. After that I applied to go to Officer Candidate School and was at Fort Benning, Georgia, in January of 1943, graduating in April as a 2nd Lt., Infantry, or “90-day Wonder,” as we were called by Regular Army friends. Ordered to Ft. McClellan, in Alabama, to train recruits, I soon found myself on orders to the West Coast for deployment to the Pacific, a “snafu” typical of the Army, and hardly a logical assignment for someone who spoke German and had a working knowledge of French. I managed to get my orders changed, and instead was ordered to and went through a rush course in Intelligence Training at Camp Ritchie, MD. In late November 1943 I shipped out for England on the Queen Elizabeth, Second in Command of a Prisoner of War Interrogation Team that there was assigned for duty with Headquarters of XIX Corps, then part of First Army, later of Ninth Army. Preparing for the invasion, we practiced interrogation on German prisoners that had been taken in Africa, and performed instructional skits before units of the Corps that also included the Corps’ reconnaissance unit, the 113th Mechanized Cavalry Group. At that Group Commander’s request I with half of our team was attached to his unit as soon as we hit the beaches in Normandy. Usually scouting in front of or flanking Infantry units, we tried to get tactical information for immediate use from just captured prisoners, while the other half of the team stayed at a prisoner enclosure near Corps Hq, looking for information of more strategic value. During our advance through Normandy into the Foret de Breteuil I managed to talk nearly 100 Germans into surrendering by “hog-calling,” venturing slowly into the woods we thought heavily defended, with my jeep sandwiched between two tanks, and me using an improvised loudspeaker, promising good treatment to any German soldier who would surrender, the thing I advised them to do, because, as I boldly told them, Germany had lost the war anyhow. It worked, and we collected the PWs and got through the woods without a single casualty. Whenever the Cavalry Group was in reserve or out of action for any length of time, my team and I were on duty back at the Corps War Room, keeping situation maps current and briefing Corps staff and liaison officers from other units. In October ’44, as we were approaching Germany, I was put in charge of a Military Intelligence Interpreter Team, the additional functions being interrogating civilians that we ran into, and dealing with officials of towns we captured. PART 4 12th Army Group, of which Ninth Army and therefore XIX Corps were part, was ordered to advance towards the Rhine River after the 1st Division captured Aachen, situated in a sector especially heavily defended by the Germans. They were most fiercely defending, and inflicting very heavy losses on our troops in the Huertgen Forest, the area close to two dams on the Roer River that Allied bombers had been unable to blow or damage, in spite of some heavy bombing raids, but that just the same had not been considered to be much of an obstacle to our advance. The dams were close to where I had grown up, and I somehow remembered the secrecy and haste with which the Germans had built one of the dams in the 1930s. Thinking that the dams might be of military significance and were in the district of which Aachen was the capital, I decided to investigate. You can just imagine how I felt, now an American Army officer, about getting back into Aachen, from where in 1938 I had been shipped to Buchenwald by the Gestapo. With my men I headed for a pile of rubble that I guessed had been the District Water Administration, found a safe that we managed to blow open, and came back to the Corps’ Chief of Intelligence with a load of documents that had him send me immediately to Ninth Army HQ, to brief the Army Engineer before I even had an opportunity to translate our find. It took me a week to translate the many documents of the German study that showed exactly what would happen if the dams were blown, the number of billions of gallons of fwater that would cascade downriver, the rate of flow, how large an area would be inundated, for how long the area would be impassable, and much more detailed information that proved to be so important that attack orders to First and Ninth Armies, involving upward of 250,000 men, were cancelled immediately, and the push to the Rhine scheduled for early November was put on hold.. It was not until February 1945, after the Ardennes Offensive of the Germans was defeated and they blew the dams to cover their own retreat, when 12th Army Group advanced towards the Rhine. Had the Germans been able to blow the Roer River dams during our originally planned advance, we could have suffered heavy losses in men and equipment. Finding the German study prevented a possible disaster from happening. When the 1st Division got ready to cross the Roer River, I asked to be attached to the unit that was to advance on Drove, my hometown, offering that my knowledge of geography and topography might be helpful. Needless to say, I most wanted to find out what I could about my parents’ fate. We got into a town that was totally deserted, had been ordered evacuated by the Germans because of the heavy fighting in the area, and all I could do was get into my empty parental home that did not look any more the way I remembered it. Rough boards had been used to make a number of small partitions in the attic. And no one was there to talk to. Only after the war did I find out that for some time in late 1941, all Jews living in town, 26 people, had been evicted from their homes, were forced to move and were crowded into my parental home, confined there under horrible conditions until they were deported, with some good Christian neighbors at night sneaking food to them to augment the meager rations the Nazis allowed them. I left the 1st Division Regiment and rejoined my men with the Cavalry that was advancing fast across Germany. On April 8th we had reached the vicinity of Einbeck, in Saxony, when I interrogated a civilian who had come across our lines. He told me that a big Military Headquarters was in town, that the town’s population with refugees from the East had grown from 12,000 to 32,000, and that the commanding Lt.General was determined to put up a fight, regardless of possible damage and casualties. Was there anything we could do to save the town? He impressed me with his sincerity and attitude and looked very scared and worried. On stupid impulse, and with a white rag tied to my jeep, I with my driver headed towards town until stopped by German troops who took me to their Headquarters. There, I brashly stated that I had orders from my commanding officer to speak to their commanding general. Brought before Lt. General Gehschritt and his deputy after some quizzing by staff officers, primarily about where I had learned to speak German so well, I told him that my Commander demanded the immediate surrender of the entire garrison if he wanted to save the city; and that I was to wait for an answer; that we were prepared to attack, and that he would be held responsible for all loss of life and destruction in the city if he decided to make a stand. Taken into another room, I had to cool my heels for about 15 minutes, until called back to the general’s office, where he then told me that in order to save the city and its many people, he had decided to surrender and would accompany me to my Headquarters. Sending my driver ahead, I ended up leading a parade to our lines, sitting uneasily next to the driver in a slow moving Mercedes staff car, with two generals in the back seats, followed by 35 officers on foot, and over 300 men marching into our lines, were they were received and processed by a Military Police unit that was attached to the 113th and that had been warned by my driver. I took the generals to the Cavalry’s Command Post, and after formal introduction asked them to turn their weapons over to Col. Biddle, the Commanding Officer. The generals were outraged at having to surrender to someone of lesser rank, but Col. Biddle got their pistols, prized souvenirs. When back in Einbeck after the surrender, I appointed Herr Keim, the man who had come across the lines and asked for help, to be acting mayor, a job that seems to have become almost permanent. 20 years after that day in April 1945 I received a telegram from him, still mayor of Einbeck, sending greetings, and once more expressing the gratitude of the people of Einbeck to me for having saved the city and its people. The war was over for me a few days later, April 12th, the day President Roosevelt died, when I was seriously wounded in cross fire by SS men in Wernigerode, in the Harz Mountains. I had been on my way to City Hall to give instructions to the mayor about the disposition of any firearms in the hands of civilians. We had taken the town the night before, but the SS men that got me had somehow managed to hide out in town during the night.

Three months

of hospitalization in England followed before I was finally shipped

home, and after marriage, surgery and long convalescence during

which I took Poultry Husbandry Courses at Rutgers University, I

in late 1946 was in Germany once more “courtesy Uncle Sam”,

this time in charge of the Documents Section of the European Command

Intelligence Center, among other things collecting information and

documents that helped convict Nazi war criminals at Nurenberg. I

was fortunate to have Mina, whom I lost after 64 years together,

able to join me during the two years I was stationed near Frankfurt.

While on this tour of duty, a search of and by all possible and

available sources and means did not produce any information about

my parents, who at that time I only knew had been deported to somewhere

in Poland early in 1942 Only because of time constraints here did I omit mentioning and describing the individual men who served with and under me. They served our Country well, were loyal, and in an exemplary and proficient way helped me do my - our - job. Off and on during

convalescence after surgery, annual leave, and on weekends we had

been driving around New Jersey, looking for a farm we could afford,

trying to do what used to be the standard saying among our military

friends. That was to “Retire on a chicken farm, letting the

chickens do all the work.” My dreams of becoming a veterinarian

killed by Hitler, and having taken the poultry courses at Rutgers

more than four years earlier, we ended up doing just that, working

with animals, only finding out that it was not the chickens, but

it was we who did almost all the work. We bought and modernized

an old, run-down farm in New Egypt, in Ocean County, that had been

idle for several years, and which over time we built up, starting

initially with pens for 2,000 chickens, and ending up housing 45,000

birds. We built our own feed mill, and a packing plant in which,

once we were at full capacity, we processed over 30,000 eggs daily,

all marketed locally. After 35 years, 27 of them without a single

vacation, when our own age and obsolescence of our buildings and

equipment told us it was time to quit, we gradually phased out operations

and ended up selling the property that was supposed to become a

horse farm. But that’s another story. As to surviving the Holocaust - no, even though my life had at times been extremely unpleasant and threatened, I do not consider myself a SURVIVOR of the Holocaust, because the planned horrific mass murders did not begin until some time after I had left Germany. I was just lucky to ESCAPE them, and with that the Holocaust. Let me just finish by saying that I know of no country other than the United States where, being such a very recent immigrant, I could have become a ranking military officer. I am proud and thankful that I was able to be of service to this – My Country - , that I had the opportunity to fight the Nazis who were murdering my family and threatening the whole world. My father’s parting words to the 18 year-old, as my train left the railroad station, had been: “Don’t do anything I’d have to be ashamed of.” - I hope I would not have disappointed him. Thank you for listening. Ernest Kaufman,

Major, AUS - Ret. |

.

.